China Is Detaining Muslims in Vast Numbers. The Goal: ‘Transformation.’

HOTAN, China — On the edge of a desert in far western China, an imposing building sits behind a fence topped with barbed wire. Large red characters on the facade urge people to learn Chinese, study law and acquire job skills. Guards make clear that visitors are not welcome.

Inside, hundreds of ethnic Uighur Muslims spend their days in a high-pressure indoctrination program, where they are forced to listen to lectures, sing hymns praising the Chinese Communist Party and write “self-criticism” essays, according to detainees who have been released.

The goal is to remove any devotion to Islam.

Abdusalam Muhemet, 41, said the police detained him for reciting a verse of the Quran at a funeral. After two months in a nearby camp, he and more than 30 others were ordered to renounce their past lives. Mr. Muhemet said he went along but quietly seethed.

“That was not a place for getting rid of extremism,” he recalled. “That was a place that will breed vengeful feelings and erase Uighur identity.”

This camp outside Hotan, an ancient oasis town in the Taklamakan Desert, is one of hundreds that China has built in the past few years. It is part of a campaign of breathtaking scale and ferocity that has swept up hundreds of thousands of Chinese Muslims for weeks or months of what critics describe as brainwashing, usually without criminal charges.

Though limited to China’s western region of Xinjiang, it is the country’s most sweeping internment program since the Mao era — and the focus of a growing chorus of international criticism.

China has sought for decades to restrict the practice of Islam and maintain an iron grip in Xinjiang, a region almost as big as Alaska where more than half the population of 24 million belongs to Muslim ethnic minority groups. Most are Uighurs, whose religion, language and culture, along with a history of independence movements and resistance to Chinese rule, have long unnerved Beijing.

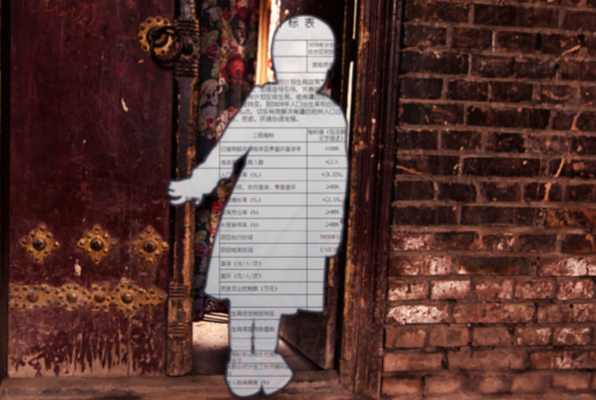

A sign describes this facility on the edge of Hotan, a city in Xinjiang, as a “concentrated transformation-through-education center.”

A sign describes this facility on the edge of Hotan, a city in Xinjiang, as a “concentrated transformation-through-education center.”

“Xinjiang is in an active period of terrorist activities, intense struggle against separatism and painful intervention to treat this,” Mr. Xi told officials, according to reports in the state news media last year.

In addition to the mass detentions, the authorities have intensified the use of informers and expanded police surveillance, even installing cameras in some people’s homes. Human rights activists and experts say the campaign has traumatized Uighur society, leaving behind fractured communities and families.

“Penetration of everyday life is almost really total now,” said Michael Clarke, an expert on Xinjiang at Australian National University in Canberra. “You have ethnic identity, Uighur identity in particular, being singled out as this kind of pathology.”

China has categorically denied reports of abuses in Xinjiang. At a meeting of a United Nations panel in Geneva last month, it said it does not operate re-education camps and described the facilities in question as mild corrective institutions that provide job training.

“There is no arbitrary detention,” Hu Lianhe, an official with a role in Xinjiang policy, told the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. “There is no such thing as re-education centers.”

The committee pressed Beijing to disclose how many people have been detained and free them, but the Ministry of Foreign Affairs dismissed the demand as having “no factual basis” and said China’s security measures were comparable to those of other countries.

The government’s business-as-usual defense, however, is contradicted by overwhelming evidence, including official directives, studies, news reports and construction plans that have surfaced online, as well as the eyewitness accounts of a growing number of former detainees who have fled to countries such as Turkey and Kazakhstan.

The government’s own documents describe a vast network of camps — usually called “transformation through education” centers — that has expanded without public debate, specific legislative authority or any system of appeal for those detained.

The New York Times interviewed four recent camp inmates from Xinjiang who described physical and verbal abuse by guards; grinding routines of singing, lectures and self-criticism meetings; and the gnawing anxiety of not knowing when they would be released. Their accounts were echoed in interviews with more than a dozen Uighurs with relatives who were in the camps or had disappeared, many of whom spoke on condition of anonymity to avoid government retaliation.

Kaynakça

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/08/world/asia/china-uighur-muslim-detention-camp.html